每天推荐一个 GitHub 优质开源项目和一篇精选英文科技或编程文章原文,欢迎关注开源日报。交流QQ群:202790710;电报群 https://t.me/OpeningSourceOrg

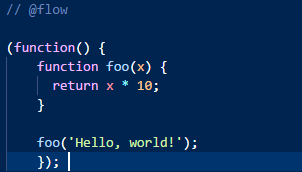

今日推荐开源项目:《Flow——针对JavaScript的静态错误检查器》

推荐理由:Flow是一款针对JavaScript的静态错误检查器,可以在Mac OS X、Linux (64-bit)或是Windows (64-bit)中运行。

Flow的优势

- 安装便捷(在Mac OS X系统,你可以通过Homebrew或OCaml OPAM 包装安装Flow;而在Windows的安装会略微繁琐一点)

- 使用简单

- Flow可以把它的剖析器编译进JavaScript里

详见官方文档:https://flow.org/en/docs/

关于glow

glow 的作用就不赘述了,今天主要说说glow 的安装与使用:

- 首先,你需要安装 flow( glow 是基于 flow 的)

- 然后,你有了两个选择:

- 全局安装glow : yarn global add glow

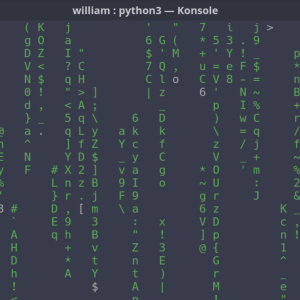

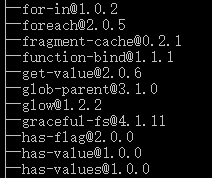

安装成功:

- 只在你要的项目中安装glow :在项目路径下,输入 yarn add –dev glow

安装成功会出现类似画面:

- 然后你便可以愉快的使用glow 了,而使用也只是在flow 的基础上改为执行 glow

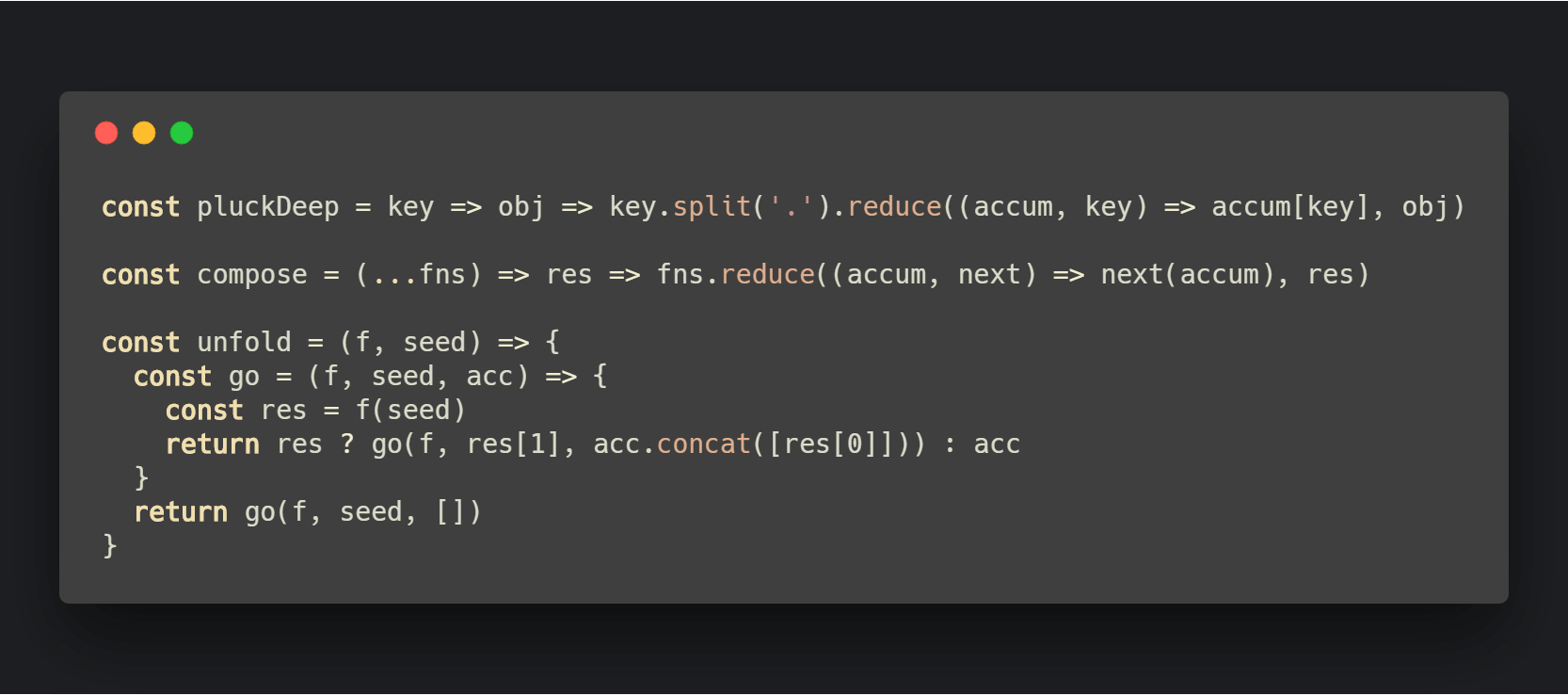

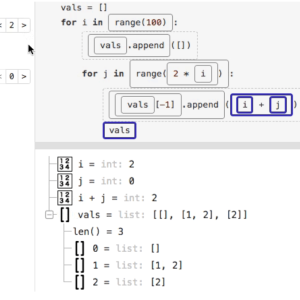

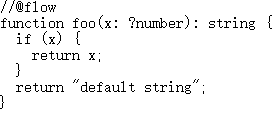

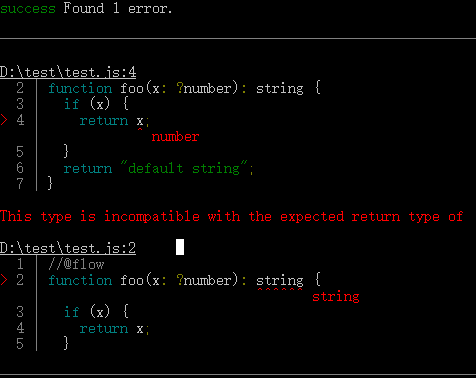

测试代码:

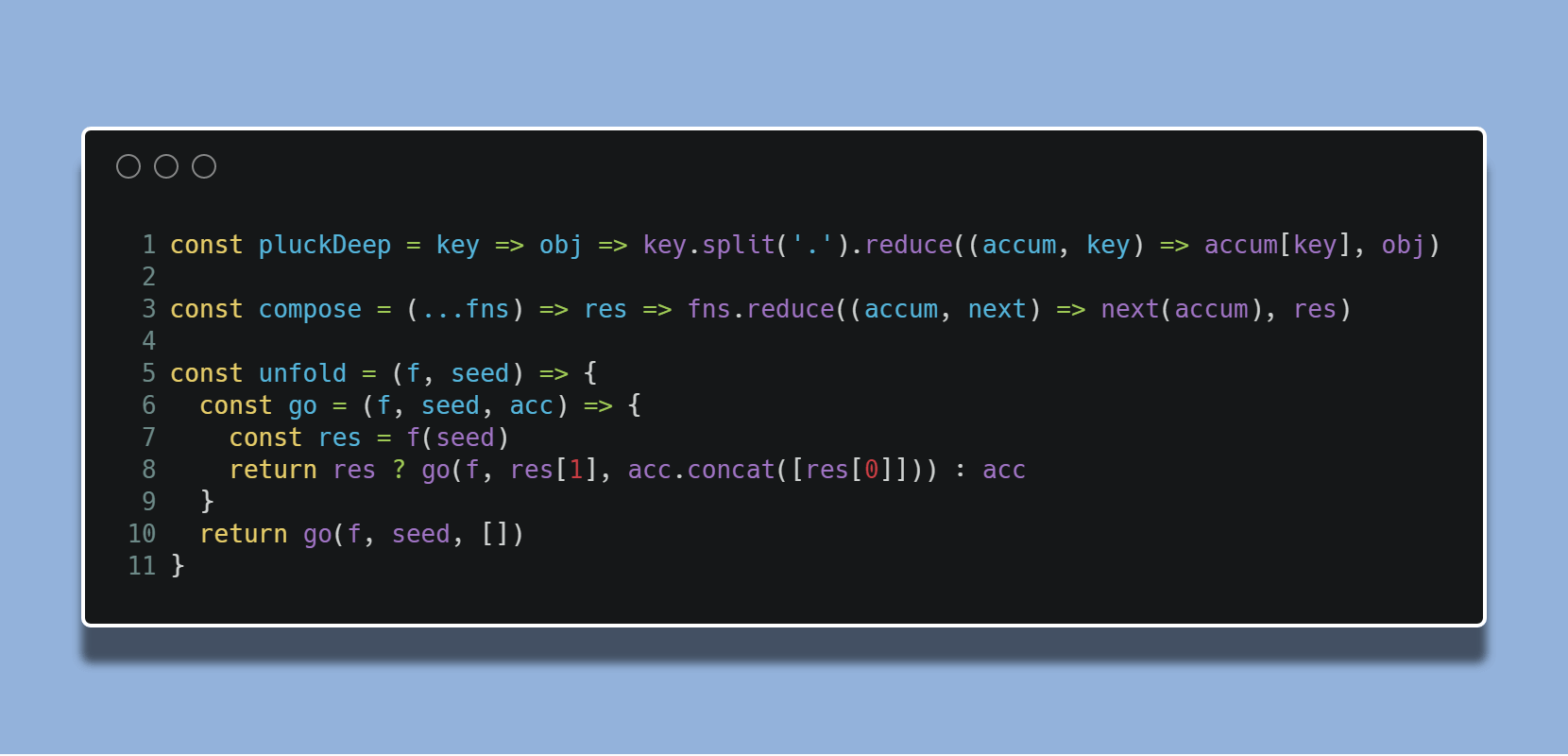

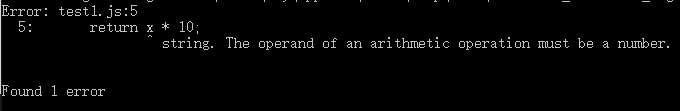

运行 flow :

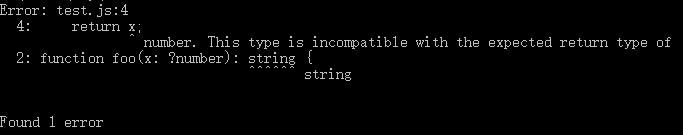

运行 glow :

关于作者

詹姆斯·凯尔:http://thejameskyle.com/

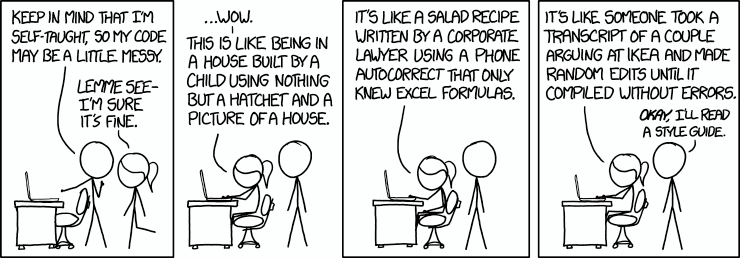

今日推荐英文原文:《How to Hack an Engineer》作者:Nemild

原文链接:https://www.nemil.com/musings/hack-an-engineer.html

推荐理由:这篇文章事实上也是一个 GitHub repo,它收集了很多宝贵的资源,如果你想做一个好工程师或者黑客的话,这些宝贵的资源应该可以帮到你。

How to Hack an Engineer

This essay introduces a Github repo to catalog all the ways that engineering inputs can be influenced. Contributions are welcome.

In 2015, I found myself talking to a smart entrepreneur who had just raised millions of dollars in venture capital from a prominent venture capital (VC) firm. He was flying high after getting substantial press and recruiting a number of early employees. His business also wholly depended on a popular open source project.

As part of his strategy, the CEO gave a core open source developer in the project equity. With this, he boasted that he would get critical information sooner, influence the roadmap for his company’s benefit, and recruit developers from the project to his company.1

I was doubtful this connection would ever be publicized by the open source developer. Would he speak glowingly about the company at a conference, despite private reservations? How would he influence the decisions of his fellow developers? Would developers early in their career follow his missives without adequate reflection?2

Computer engineers regularly deal with exploits on their technical systems, where an external party takes advantage of a bug or vulnerability. An “exploit” or social engineering of our personal information sources — motivated parties influencing subreddits, conferences, meetups, blogs, journalists, professors, industry analysts — should be perceived similarly. As this example shows, even your peers can be influenced.

As engineers, it’s valuable to develop the antibodies that enable us to make the best decisions — both for our teams and for our own careers — despite the desires of these motivated parties. Beyond identifying ways we can be influenced, I list out three techniques to help us make better decisions.

The War to Influence Engineers

This is just one example in a larger war that rages in this global era of computing: that for the hearts of engineers.

Some of the many groups that will try to shape our views include:

- Developer tools teams who want to sell their technology or grow their platform

- Companies who wants to hire us

- Open source developers who want to recruit contributors and users

- Venture capitalists who want to fund us

- Training programs that want to sell their courses

- Consulting firms that want us to hire them

- Social networks that are trying to maximize engagement, readership, and revenue

The content they create and sponsor (press releases, meetups, blog posts, conferences, speaker talks) play a critical role in the decisions we make — from the technology we adopt to the companies we join.

A press release indicating large traction (often with many missing numbers) may be a primary reason to join a startup. A blog post or popular talk on the latest database technology — like NoSQL — may be a reason to experiment and later switch. A college lecturer may partly be there to pitch their own company’s technology. The most upvoted Hacker News (HN) posts over a year may influence what technologies we choose to adopt. And yet, as consumers of this information, many of us don’t always critically examine the information and its source.

In startups, bad technology choices made based on these inputs can divert the focus, putting the mission at risk. For an individual engineer, learning the wrong technology can waste our time. Joining the wrong company that sells us false promises can set our career back.

Example: Recruiting engineers and raising venture capital in startups

A friend in VC once laughed after seeing an article extolling how well a startup was doing. After having been pitched by that company, he knew they were struggling and the article was their way to attract investor interest and continue hiring good talent before their funding ran out. I know many people who would have taken the exact opposite impression from the post. Crucially, with the right training, it would have been possible to suss out some of the reality behind this article.3

In a public example, Theranos popularized the idea of the pinprick blood test and had potentially huge social benefits. It must have been exciting for technical talent to join the company.

Yet many were attracted by universally adulatory press (example) that had been shaped by a motivated management team and media organizations that uncritically covered them.4 While much has been written about investor losses, Theranos’s exceptional engineers and scientists also likely lost important years to do truly impactful work and had their resumes sullied.

Example: Dev Tool Marketing at MongoDB

MongoDB was one of the fastest growing NoSQL databases in the late 2000s that promised a “modern” database experience.

In my deep dive into the early marketing strategy behind MongoDB, I pointed out issues relevant in dev tools marketing including:

- Speakers invited to many MongoDB meetups/conferences would have their own motivations (trying to sell their consulting services, marketing for their own dev tools products)

- Hack academies and early programmer blogs were valuable allies for pitching the MEAN stack, while not seeming like a sales pitch when seen on HN/Reddit

- MongoDB would argue that nearly every use case should be solved with their database, without highlighting the tradeoffs in different use cases

- College hackathons were a way to influence early developers who may not have fully understood the tradeoffs they were making

Have your own example? Email me at example at this domain. (my public key)

Even though I point out the issues in these case studies, I am far from a dispassionate scientist when on a mission for my team. Given that, it’s at least important to ensure that all engineers have the general tools to understand some of the messages we see. And in this era of fake news, selective facts, and troll armies, these lessons can also help us assess information far beyond engineering content.

Hidden Influences

Unlike previous generations of marketing, the external influences in engineering media today are often disguised.

The purpose of a press release or a sales call is clear. When this content is used to give a talk at a conference or inspire someone else to write a blog post, they blur the line. With a powerful marketing budget or fundraise, it becomes increasingly easy to publicize and convince others with one’s message, regardless of the veracity.5

I’ve had a personal experience with this in a different part of the world. After my engineering studies, I worked for the World Bank in Dili, East Timor. One day, we were explaining to a group of journalists6 the benefits of a project we were funding. There were many debates to be had for a thoughtful Timorese citizen7, but our focus was on how the World Bank perceived it. We predictably sent the journalists home with a press release extolling the project’s virtues.

The next day, our press release appeared verbatim in a local Timorese newspaper with no mention that it was a press release — under the author’s byline. It made sure that the World Bank’s key points were shared. And yet it raised troubling questions for me about how Timorese citizens used media to make decisions.8

Only later would I realize how prevalent this is around the world. In Silicon Valley, well placed friends tell me that they shudder at the information sources available to most — and how uncritically different messages are internalized. I worry especially about junior engineers (such as those in college and on r/learnprogramming) and those far from top tech centers, who may not realize how “the sausage is made.”

Example: Microservices hype

The engineering community has gone through large debates about the benefits of microservices. My own view is that the popularity of microservices in startups was a function of the hype and marketing spend around containerization. For example, compare a blog post on microservices at startups to Martin Fowler’s more nuanced view.

Many of these messages come from other engineers, open source teams, or training programs who are often trusted in a way few others are. This highlights a common mistake in startup engineering, where products/techniques pitched at mid-size company CTOs appear in pre-product market fit startups regardless of their appropriateness.

Example: Developer training programs

Training programs aren’t immune from the desire to engage readers and maximize the distribution for their content as they seek to increase readership and attract students. Some of the teachers they work with have their own motivations to push a certain technology — and their background may not be vetted.

Free Code Camp, a popular developer blog with 350k followers, carried a recent post that argued REST is dead and GraphQL is the future (“REST in Peace. Long Live GraphQL”). The article had been posted by the head of Free Code Camp and written by an author who was concurrently selling a GraphQL training program (my critique here).

Reflecting back on my own early days, I worry about junior engineers who might feel like they have to learn GraphQL based on an article like this rather than realizing all the conflicts involved. An older example from them is “The Real Reason to learn the MEAN stack: Employability” — which many of my most thoughtful friends would have strenuously disagreed with. I especially worry about what content like this does in early developer communities, where there many not be enough thoughtful engineers to disagree with these viewpoints.

Example: Content marketing in tech

Beyond direct influence, a surprising percentage of posts on engineering social media are content marketing. These posts aim to add value — but are written for the primary purpose of helping their companies sell their product. Readers can sometimes internalize them as “journalism,” even though their objective is to make a sale, influence a mindset shift, or improve SEO.

Union Square’s Fred Wilson notes how pervasive content marketing is in tech and encourages critical assessment of the message (emphasis added):

So how should entrepreneurs use this knowledge that is being imparted by VCs [like myself] …? Well first and foremost, you should see it as content marketing…

That doesn’t mean it isn’t useful or insightful. It may well be. But you should understand the business model supporting all of this free content. It is being generated to get you to come visit that VC and offer them to participate in your Seed or Series A round. That blog post that Joe claimed is not scripture in his tweet is actually an advertisement. Kind of the opposite of scripture, right?

For all these reasons and more, my most thoughtful friends use their own networks to understand reality instead: college/graduate school friends from select universities, frank talks with portfolio CEOs (for investors), ‘off the record’ conversations with connections at the various platform providers, trenchant blogs from front line engineers. Their information sources are less influenced by self-interest, providing a more objective view of the world. People can also say things privately they wouldn’t feel comfortable sharing broadly.

These friends of mine also have a deep-seated desire (specifically, a financial or technical motivation) to get at the truth, and so aim to understand the incentives driving every one of their sources. Though they may be outwardly agreeable, internally they’re deeply critical thinkers.

How Engineers Can Make Better Choices

These issues have a basic lesson: nothing is a replacement for surrounding oneself with primary sources, a community interested in the truth, and thoughtful engineers.

I’ve created a Github repo listing a few of the oft used inputs for startup engineering decisions that I’ve seen over my own startup journey. For each, I’ve noted how they work — and how they can be exploited. Contributions are welcome.

Beyond the self-interested factors, engineering media can be distorted for other reasons. For example, each upvote on Hacker News is equal — meaning that the world’s most thoughtful expert on a topic has the same voting power as someone inexperienced. Nearly every social media algorithm favors engagement over any other metric, meaning that what we read is simply a function of what those around us want to read (this echoes my research on what types of deaths are covered in a leading US newspaper).

Example: Cryptocurrency tribes and social media

In social media, the group you surround yourself by can shape your attitudes, even though engineering decisions should be based on empiricism and facts. Social media groups and algorithms pick content that confirms its users’ beliefs — and paint the opposite side in the worst light. This tribalism can be regularly seen in cryptocurrency subreddits, meaning that readers consume a distorted reality (see also filter bubbles).

As the cofounder of Coinbase, Fred Ehrsam, explains:

Cryptocurrencies create strong tribalism. Once you own a currency, your incentives are to make that currency go up in value. Crypto tribalism can be seen on reddit every day. Subreddits generate and report news that support their holdings. Crypto tribalism plays out in two common ways: 1) people promoting their own currency and 2) people discrediting other currencies. People promoting their own currency is evidenced by the imbalance of positive to negative news about a currency on its own subreddit.

For now, I’ll suggest three simple points that go far in assessing engineering media:

1. Identify incentives behind content that informs important decisions

First, consider a writer/speaker’s motivation — both directly (an employee or investor in the company) or indirectly (a public speaker who is a consultant looking for a gig or employee looking for a job/advisorship).

When I read a post or hear a speaker, I often ask myself a few questions:

- Background: What is their technical background and why are they well suited to speak on this topic?

- Objectives: What are their personal objectives in speaking/blogging? (e.g., recruiting, personal brand, new business); there almost always is one

- Conflicts: What conflicts might they have and how does this influence the message?

- Allies: Who else wants this content out there?

- Distributor Incentives; Why is the distributor (social network, media publication) putting this content in front of me? (who are the upvoters, what is the business model, etc.)

When we see a lot of press from a company, it’s often a sign that they want something from us. Their employees have consciously spent the time to sit down with a journalist or taken the time to write a post.9

2. Debunk claims

Second, inculcate a desire to debunk claims.

For example, companies regularly trumpet their (tailor-made) benchmarks that show their products in the best light. It’s often not that difficult to run our own benchmarks that reflect our real world use cases.

The direct reading of codebases is a powerful corrective (where available). It’s a primary source that doesn’t have ‘spin’ built in.

Looking back on trends in technology and where they ended up is another approach, which is akin to backtesting10: it’s easier to tune out hype, when we think about how people in a few years may perceive it, based on things we’ve seen in the past.

Say something in online communities when you disagree or see egregious incentive issues (here’s one favorite recent example on AV1 vs HEVC). On HN, this could be comments or a post of your own, even if it’s with a throwaway account. New social network designs might let us award karma to people who list out the key incentive issues in the future.

3. Build a community of respected peers and thoughtful experts

Third, examine the community that you lean on to determine important technical decisions.

It’s important to have a community of people who benefit from the truth, think critically, and have content expertise. This could be former employees, classmates, or your coworkers. You can augment this with the most thoughtful engineers you can find. Online, you can often find some of these groups in the comments of niche HN posts and open source mailing lists/chat rooms. In your early years, finding a thoughtful mentor is critical.

In many ways, this approach mirrors the web of trust in computer security, where we look to trusted friends — and people these trusted friends are connected to.

This point underlines the benefits of a thoughtful engineering curriculum taught by dispassionate teachers. I’m unaware of any school who teaches early engineers how they should best consume engineering media — or how to choose a technical tool. Often, this means that we’re then vulnerable for a few years, until we’ve incorporated the lessons from working on a good team.

Having a few thoughtful experts in our community is also critical when assessing deeply technical decisions like what database to use or how best to architect a system. The danger with some experts — the non-thoughtful variety — is that their confidence in their abilities means they don’t question many deep seated assumptions and can’t make adjustments when the world changes. Thoughtful experts have both content expertise and strong opinions that are weakly held.

Coda

We engineers share some similarities with the machine learning algorithms we design. In both, data is used to make inferences about future decisions. As such, it’s important to have a thoughtfully curated training data set — and to adjust for any errors when our engineering inputs are compromised.

I’ve hardly touched on all the other questions we should be discussing, beyond encouraging critical thinking and finding trusted networks of thoughtful engineers. For example, should we debate alternate Hacker News and Twitter algorithms with the hope of creating better engineers? Should there be conflict disclosures for open source developers? Should popular engineering blogs such as Free Code Camp have a board of engineers who technically assess content and the background of writers? Should we teach engineering media literacy in bootcamps and CS programs?

Still, I’m encouraged by the fact that critical thinking and testing hypothesis is such a natural part of how engineers and scientists approach the world. This mindset has a critical role to play far beyond the day to day engineering problems we aim to solve.

See the Hacking Engineers and Engineering Media Github. Contributions are welcome.

来下载图片,也可以按

来下载图片,也可以按 共享链接

共享链接