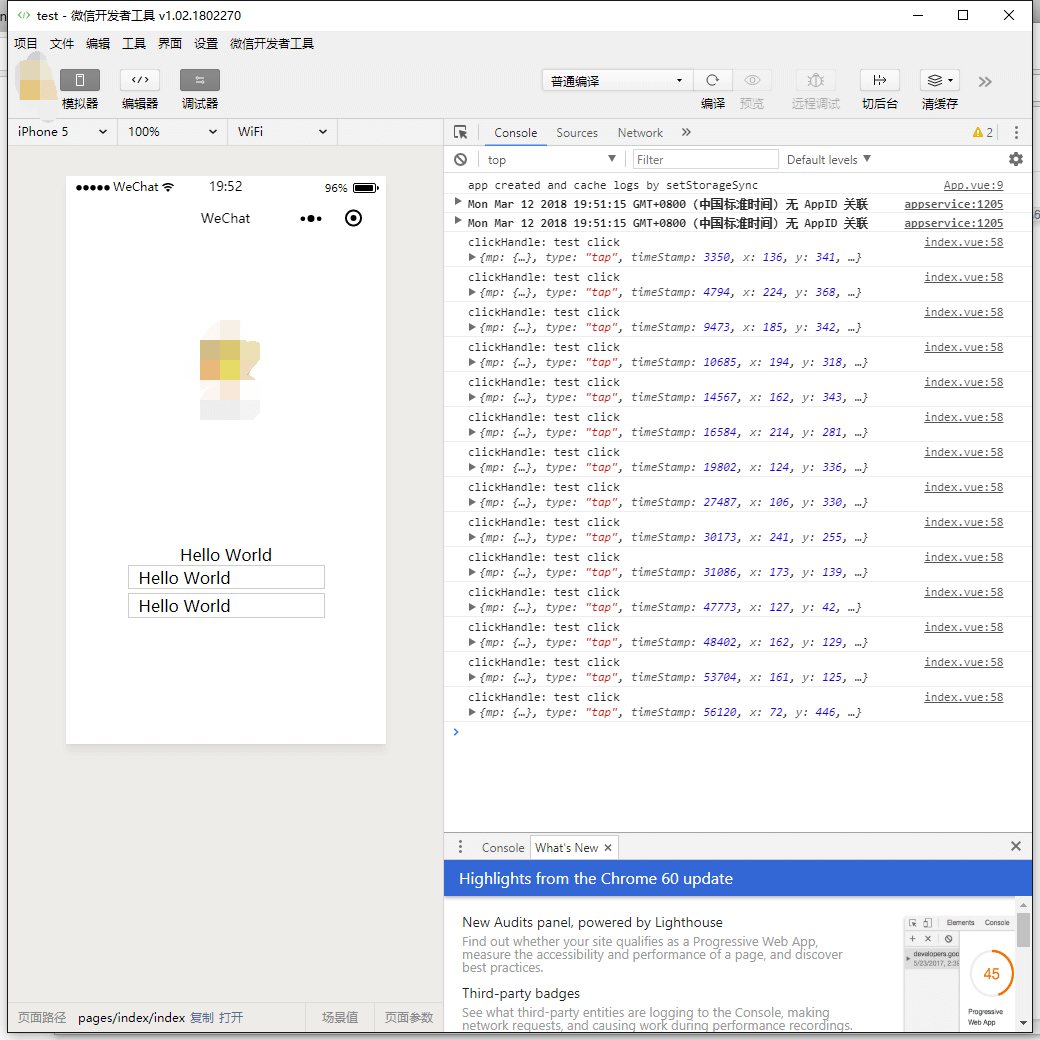

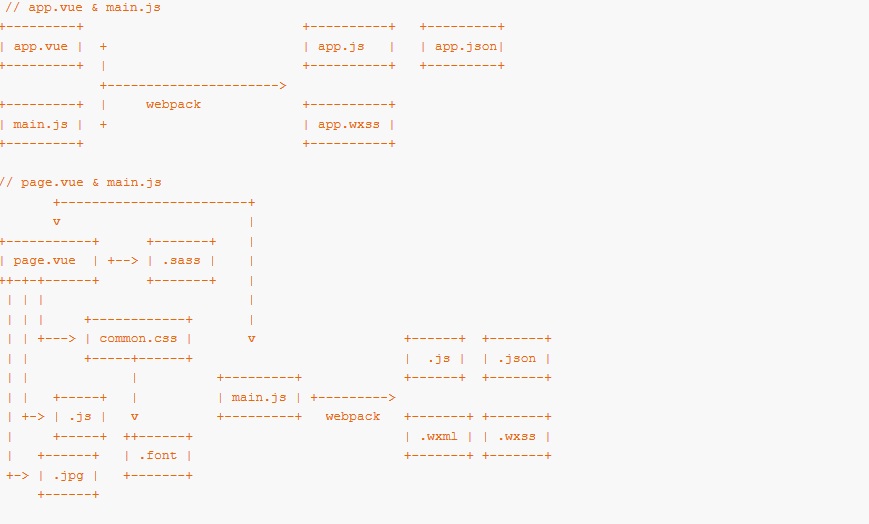

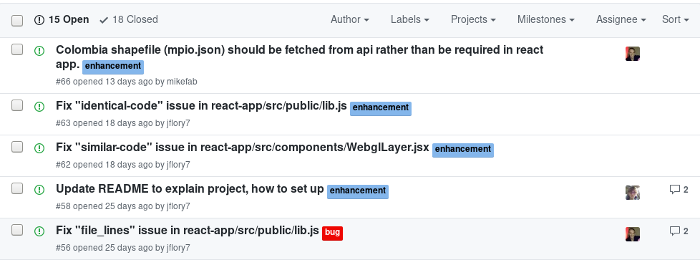

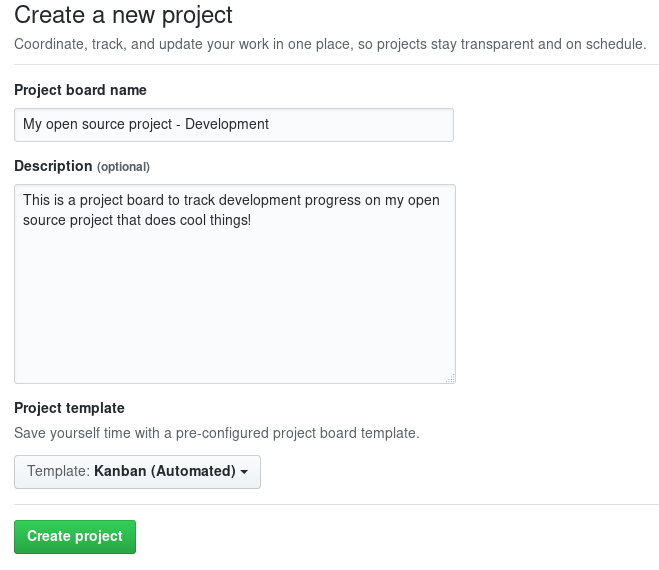

每天推荐一个 GitHub 优质开源项目和一篇精选英文科技或编程文章原文,欢迎关注开源日报。交流QQ群:202790710;电报群 https://t.me/OpeningSourceOrg

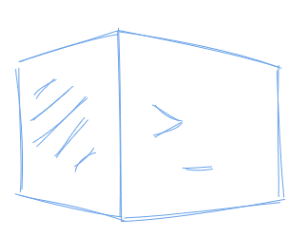

今日推荐开源项目:《Rough.js轻量级手绘画风图形库》

推荐理由:Rough.js是一种重量轻(〜8K),基于Canvas的JS库,可以让你画粗略,手绘般的风格。该库定义了绘制线条,曲线,弧线,多边形,圆形和椭圆的基元。它也支持绘制SVG路径。

使用

首先,你需要使用npm安装它

你需要创建一个画布:

<canvas id=”canvas” width=”800″ height=”600″></canvas>

然后,在<script>x下通过id获取画布:

const rc = rough.canvas(document.getElementById(‘canvas’));

之后,通过形如

rc.line(60, 60, 190, 60);

rc.rectangle(10, 10, 100, 100);

rc.rectangle(140, 10, 100, 100, {

fill: ‘rgba(255,0,0,0.2)’,

fillStyle: ‘solid’,

roughness: 2

});

的语法愉快的画画画吧

例如,上面的代码画了两个画风清奇的矩形,并设置了一系列属性,得到如下的图案:

然后,让我们画一个开源工场的logo吧

rc.line(371.92,140.77,198.92,100.77,{roughness:2,stroke:’#68a1e8′});

rc.line(371.92,278.77,368.92,140.77,{roughness:2,stroke:’#68a1e8′});

rc.line(372.92,281.77,205.92,299.77,{roughness:2,stroke:’#68a1e8′});

rc.line(203.92,301.77,201.92,100.77,{roughness:2,stroke:’#68a1e8′});

rc.line(198.92,104.77,94.92,136.77,{roughness:2,stroke:’#68a1e8′});

rc.line(94.92,141.77,97.92,272.77,{roughness:2,stroke:’#68a1e8′});

rc.line(93.92,274.77,205.92,300.77,{roughness:2,stroke:’#68a1e8′});

rc.line(134.92,152.77,113.92,173.77,{roughness:2,stroke:’#68a1e8′});

rc.line(152.92,161.77,109.92,198.77,{roughness:2,stroke:’#68a1e8′});

rc.line(167.92,172.77,114.92,224.77,{roughness:2,stroke:’#68a1e8′});

rc.line(167.92,197.77,133.92,235.77,{roughness:2,stroke:’#68a1e8′});

rc.line(174.92,227.77,155.92,247.77,{roughness:2,stroke:’#68a1e8′});

rc.line(265.92,198.77,236.92,179.77,{roughness:2,stroke:’#68a1e8′});

rc.line(266.92,199.77,238.92,216.77,{roughness:2,stroke:’#68a1e8′});

rc.line(301.92,247.77,271.92,248.77,{roughness:2,stroke:’#68a1e8′});

效果:

好了,开始愉快的画画画吧!

注:这个画出来的东西画风都很清奇(笑)

作者介绍

Preet Shihn

旧金山的一名工程师,喜欢听歌,喜欢玩《掘地求生》,热爱关注新闻,喜欢用表情包,在推特上diss川普。他和别人一起搞了个网站,名字叫Channels(https://channels.cc/),这是世界上第一个对内容的多选择微支付市场,你可以在这里发表作品,如果有人看,你就能赚钱

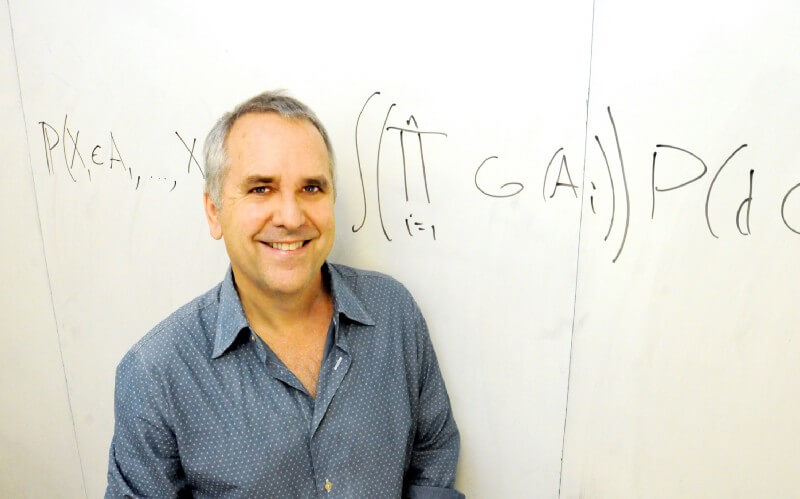

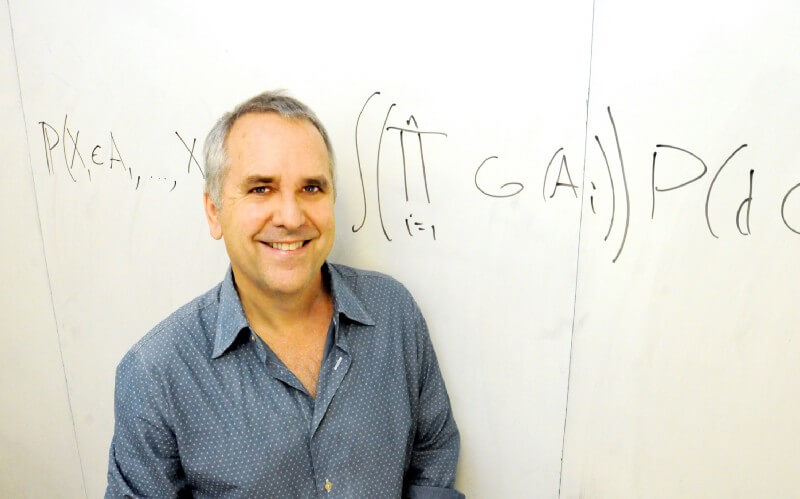

今日推荐英文原文:《Artificial Intelligence — The Revolution Hasn’t Happened Yet》作者:Michael Jordan

原文链接:https://medium.com/@mijordan3/artificial-intelligence-the-revolution-hasnt-happened-yet-5e1d5812e1e7

推荐理由:人工智能的革命还远远没有发生?这几年人工智能的发展如火如荼,类似“人工智能手机”、“人工智能摄像头”的说法都层出不穷,无数外行人内行人为这个领域的发展而激动不已,然而美国科学院院士、加州大学伯克里教授 Michael Jordan 却说“人工智能的革命还远远没有发生”,请听听看他是怎么说的。Michael Jordan是人工智能和机器学习领域很有建树,甚至被誉为“机器学习之父”,也是著名华裔科学家吴恩达的恩师。

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the mantra of the current era. The phrase is intoned by technologists, academicians, journalists and venture capitalists alike. As with many phrases that cross over from technical academic fields into general circulation, there is significant misunderstanding accompanying the use of the phrase. But this is not the classical case of the public not understanding the scientists — here the scientists are often as befuddled as the public. The idea that our era is somehow seeing the emergence of an intelligence in silicon that rivals our own entertains all of us — enthralling us and frightening us in equal measure. And, unfortunately, it distracts us.

There is a different narrative that one can tell about the current era. Consider the following story, which involves humans, computers, data and life-or-death decisions, but where the focus is something other than intelligence-in-silicon fantasies. When my spouse was pregnant 14 years ago, we had an ultrasound. There was a geneticist in the room, and she pointed out some white spots around the heart of the fetus. “Those are markers for Down syndrome,” she noted, “and your risk has now gone up to 1 in 20.” She further let us know that we could learn whether the fetus in fact had the genetic modification underlying Down syndrome via an amniocentesis. But amniocentesis was risky — the risk of killing the fetus during the procedure was roughly 1 in 300. Being a statistician, I determined to find out where these numbers were coming from. To cut a long story short, I discovered that a statistical analysis had been done a decade previously in the UK, where these white spots, which reflect calcium buildup, were indeed established as a predictor of Down syndrome. But I also noticed that the imaging machine used in our test had a few hundred more pixels per square inch than the machine used in the UK study. I went back to tell the geneticist that I believed that the white spots were likely false positives — that they were literally “white noise.” She said “Ah, that explains why we started seeing an uptick in Down syndrome diagnoses a few years ago; it’s when the new machine arrived.”

We didn’t do the amniocentesis, and a healthy girl was born a few months later. But the episode troubled me, particularly after a back-of-the-envelope calculation convinced me that many thousands of people had gotten that diagnosis that same day worldwide, that many of them had opted for amniocentesis, and that a number of babies had died needlessly. And this happened day after day until it somehow got fixed. The problem that this episode revealed wasn’t about my individual medical care; it was about a medical system that measured variables and outcomes in various places and times, conducted statistical analyses, and made use of the results in other places and times. The problem had to do not just with data analysis per se, but with what database researchers call “provenance” — broadly, where did data arise, what inferences were drawn from the data, and how relevant are those inferences to the present situation? While a trained human might be able to work all of this out on a case-by-case basis, the issue was that of designing a planetary-scale medical system that could do this without the need for such detailed human oversight.

I’m also a computer scientist, and it occurred to me that the principles needed to build planetary-scale inference-and-decision-making systems of this kind, blending computer science with statistics, and taking into account human utilities, were nowhere to be found in my education. And it occurred to me that the development of such principles — which will be needed not only in the medical domain but also in domains such as commerce, transportation and education — were at least as important as those of building AI systems that can dazzle us with their game-playing or sensorimotor skills.

Whether or not we come to understand “intelligence” any time soon, we do have a major challenge on our hands in bringing together computers and humans in ways that enhance human life. While this challenge is viewed by some as subservient to the creation of “artificial intelligence,” it can also be viewed more prosaically — but with no less reverence — as the creation of a new branch of engineering. Much like civil engineering and chemical engineering in decades past, this new discipline aims to corral the power of a few key ideas, bringing new resources and capabilities to people, and doing so safely. Whereas civil engineering and chemical engineering were built on physics and chemistry, this new engineering discipline will be built on ideas that the preceding century gave substance to — ideas such as “information,” “algorithm,” “data,” “uncertainty,” “computing,” “inference,” and “optimization.” Moreover, since much of the focus of the new discipline will be on data from and about humans, its development will require perspectives from the social sciences and humanities.

While the building blocks have begun to emerge, the principles for putting these blocks together have not yet emerged, and so the blocks are currently being put together in ad-hoc ways.

Thus, just as humans built buildings and bridges before there was civil engineering, humans are proceeding with the building of societal-scale, inference-and-decision-making systems that involve machines, humans and the environment. Just as early buildings and bridges sometimes fell to the ground — in unforeseen ways and with tragic consequences — many of our early societal-scale inference-and-decision-making systems are already exposing serious conceptual flaws.

And, unfortunately, we are not very good at anticipating what the next emerging serious flaw will be. What we’re missing is an engineering discipline with its principles of analysis and design.

The current public dialog about these issues too often uses “AI” as an intellectual wildcard, one that makes it difficult to reason about the scope and consequences of emerging technology. Let us begin by considering more carefully what “AI” has been used to refer to, both recently and historically.

Most of what is being called “AI” today, particularly in the public sphere, is what has been called “Machine Learning” (ML) for the past several decades. ML is an algorithmic field that blends ideas from statistics, computer science and many other disciplines (see below) to design algorithms that process data, make predictions and help make decisions. In terms of impact on the real world, ML is the real thing, and not just recently. Indeed, that ML would grow into massive industrial relevance was already clear in the early 1990s, and by the turn of the century forward-looking companies such as Amazon were already using ML throughout their business, solving mission-critical back-end problems in fraud detection and logistics-chain prediction, and building innovative consumer-facing services such as recommendation systems. As datasets and computing resources grew rapidly over the ensuing two decades, it became clear that ML would soon power not only Amazon but essentially any company in which decisions could be tied to large-scale data. New business models would emerge. The phrase “Data Science” began to be used to refer to this phenomenon, reflecting the need of ML algorithms experts to partner with database and distributed-systems experts to build scalable, robust ML systems, and reflecting the larger social and environmental scope of the resulting systems.

This confluence of ideas and technology trends has been rebranded as “AI” over the past few years. This rebranding is worthy of some scrutiny.

Historically, the phrase “AI” was coined in the late 1950’s to refer to the heady aspiration of realizing in software and hardware an entity possessing human-level intelligence. We will use the phrase “human-imitative AI” to refer to this aspiration, emphasizing the notion that the artificially intelligent entity should seem to be one of us, if not physically at least mentally (whatever that might mean). This was largely an academic enterprise. While related academic fields such as operations research, statistics, pattern recognition, information theory and control theory already existed, and were often inspired by human intelligence (and animal intelligence), these fields were arguably focused on “low-level” signals and decisions. The ability of, say, a squirrel to perceive the three-dimensional structure of the forest it lives in, and to leap among its branches, was inspirational to these fields. “AI” was meant to focus on something different — the “high-level” or “cognitive” capability of humans to “reason” and to “think.” Sixty years hence, however, high-level reasoning and thought remain elusive. The developments which are now being called “AI” arose mostly in the engineering fields associated with low-level pattern recognition and movement control, and in the field of statistics — the discipline focused on finding patterns in data and on making well-founded predictions, tests of hypotheses and decisions.

Indeed, the famous “backpropagation” algorithm that was rediscovered by David Rumelhart in the early 1980s, and which is now viewed as being at the core of the so-called “AI revolution,” first arose in the field of control theory in the 1950s and 1960s. One of its early applications was to optimize the thrusts of the Apollo spaceships as they headed towards the moon.

Since the 1960s much progress has been made, but it has arguably not come about from the pursuit of human-imitative AI. Rather, as in the case of the Apollo spaceships, these ideas have often been hidden behind the scenes, and have been the handiwork of researchers focused on specific engineering challenges. Although not visible to the general public, research and systems-building in areas such as document retrieval, text classification, fraud detection, recommendation systems, personalized search, social network analysis, planning, diagnostics and A/B testing have been a major success — these are the advances that have powered companies such as Google, Netflix, Facebook and Amazon.

One could simply agree to refer to all of this as “AI,” and indeed that is what appears to have happened. Such labeling may come as a surprise to optimization or statistics researchers, who wake up to find themselves suddenly referred to as “AI researchers.” But labeling of researchers aside, the bigger problem is that the use of this single, ill-defined acronym prevents a clear understanding of the range of intellectual and commercial issues at play.

The past two decades have seen major progress — in industry and academia — in a complementary aspiration to human-imitative AI that is often referred to as “Intelligence Augmentation” (IA). Here computation and data are used to create services that augment human intelligence and creativity. A search engine can be viewed as an example of IA (it augments human memory and factual knowledge), as can natural language translation (it augments the ability of a human to communicate). Computing-based generation of sounds and images serves as a palette and creativity enhancer for artists. While services of this kind could conceivably involve high-level reasoning and thought, currently they don’t — they mostly perform various kinds of string-matching and numerical operations that capture patterns that humans can make use of.

Hoping that the reader will tolerate one last acronym, let us conceive broadly of a discipline of “Intelligent Infrastructure” (II), whereby a web of computation, data and physical entities exists that makes human environments more supportive, interesting and safe. Such infrastructure is beginning to make its appearance in domains such as transportation, medicine, commerce and finance, with vast implications for individual humans and societies. This emergence sometimes arises in conversations about an “Internet of Things,” but that effort generally refers to the mere problem of getting “things” onto the Internet — not to the far grander set of challenges associated with these “things” capable of analyzing those data streams to discover facts about the world, and interacting with humans and other “things” at a far higher level of abstraction than mere bits.

For example, returning to my personal anecdote, we might imagine living our lives in a “societal-scale medical system” that sets up data flows, and data-analysis flows, between doctors and devices positioned in and around human bodies, thereby able to aid human intelligence in making diagnoses and providing care. The system would incorporate information from cells in the body, DNA, blood tests, environment, population genetics and the vast scientific literature on drugs and treatments. It would not just focus on a single patient and a doctor, but on relationships among all humans — just as current medical testing allows experiments done on one set of humans (or animals) to be brought to bear in the care of other humans. It would help maintain notions of relevance, provenance and reliability, in the way that the current banking system focuses on such challenges in the domain of finance and payment. And, while one can foresee many problems arising such a system — involving privacy issues, liability issues, security issues, etc — these problems should properly be viewed as challenges, not show-stoppers.

We now come to a critical issue: Is working on classical human-imitative AI the best or only way to focus on these larger challenges? Some of the most heralded recent success stories of ML have in fact been in areas associated with human-imitative AI — areas such as computer vision, speech recognition, game-playing and robotics. So perhaps we should simply await further progress in domains such as these. There are two points to make here. First, although one would not know it from reading the newspapers, success in human-imitative AI has in fact been limited — we are very far from realizing human-imitative AI aspirations. Unfortunately the thrill (and fear) of making even limited progress on human-imitative AI gives rise to levels of over-exuberance and media attention that is not present in other areas of engineering.

Second, and more importantly, success in these domains is neither sufficient nor necessary to solve important IA and II problems. On the sufficiency side, consider self-driving cars. For such technology to be realized, a range of engineering problems will need to be solved that may have little relationship to human competencies (or human lack-of-competencies). The overall transportation system (an II system) will likely more closely resemble the current air-traffic control system than the current collection of loosely-coupled, forward-facing, inattentive human drivers. It will be vastly more complex than the current air-traffic control system, specifically in its use of massive amounts of data and adaptive statistical modeling to inform fine-grained decisions. It is those challenges that need to be in the forefront, and in such an effort a focus on human-imitative AI may be a distraction.

As for the necessity argument, it is sometimes argued that the human-imitative AI aspiration subsumes IA and II aspirations, because a human-imitative AI system would not only be able to solve the classical problems of AI (as embodied, e.g., in the Turing test), but it would also be our best bet for solving IA and II problems. Such an argument has little historical precedent. Did civil engineering develop by envisaging the creation of an artificial carpenter or bricklayer? Should chemical engineering have been framed in terms of creating an artificial chemist? Even more polemically: if our goal was to build chemical factories, should we have first created an artificial chemist who would have then worked out how to build a chemical factory?

A related argument is that human intelligence is the only kind of intelligence that we know, and that we should aim to mimic it as a first step. But humans are in fact not very good at some kinds of reasoning — we have our lapses, biases and limitations. Moreover, critically, we did not evolve to perform the kinds of large-scale decision-making that modern II systems must face, nor to cope with the kinds of uncertainty that arise in II contexts. One could argue

that an AI system would not only imitate human intelligence, but also “correct” it, and would also scale to arbitrarily large problems. But we are now in the realm of science fiction — such speculative arguments, while entertaining in the setting of fiction, should not be our principal strategy going forward in the face of the critical IA and II problems that are beginning to emerge. We need to solve IA and II problems on their own merits, not as a mere corollary to an human-imitative AI agenda.

It is not hard to pinpoint algorithmic and infrastructure challenges in II systems that are not central themes in human-imitative AI research. II systems require the ability to manage distributed repositories of knowledge that are rapidly changing and are likely to be globally incoherent. Such systems must cope with cloud-edge interactions in making timely, distributed decisions and they must deal with long-tail phenomena whereby there is lots of data on some individuals and little data on most individuals. They must address the difficulties of sharing data across administrative and competitive boundaries. Finally, and of particular importance, II systems must bring economic ideas such as incentives and pricing into the realm of the statistical and computational infrastructures that link humans to each other and to valued goods. Such II systems can be viewed as not merely providing a service, but as creating markets. There are domains such as music, literature and journalism that are crying out for the emergence of such markets, where data analysis links producers and consumers. And this must all be done within the context of evolving societal, ethical and legal norms.

Of course, classical human-imitative AI problems remain of great interest as well. However, the current focus on doing AI research via the gathering of data, the deployment of “deep learning” infrastructure, and the demonstration of systems that mimic certain narrowly-defined human skills — with little in the way of emerging explanatory principles — tends to deflect attention from major open problems in classical AI. These problems include the need to bring meaning and reasoning into systems that perform natural language processing, the need to infer and represent causality, the need to develop computationally-tractable representations of uncertainty and the need to develop systems that formulate and pursue long-term goals. These are classical goals in human-imitative AI, but in the current hubbub over the “AI revolution,” it is easy to forget that they are not yet solved.

IA will also remain quite essential, because for the foreseeable future, computers will not be able to match humans in their ability to reason abstractly about real-world situations. We will need well-thought-out interactions of humans and computers to solve our most pressing problems. And we will want computers to trigger new levels of human creativity, not replace human creativity (whatever that might mean).

It was John McCarthy (while a professor at Dartmouth, and soon to take a

position at MIT) who coined the term “AI,” apparently to distinguish his

budding research agenda from that of Norbert Wiener (then an older professor at MIT). Wiener had coined “cybernetics” to refer to his own vision of intelligent systems — a vision that was closely tied to operations research, statistics, pattern recognition, information theory and control theory. McCarthy, on the other hand, emphasized the ties to logic. In an interesting reversal, it is Wiener’s intellectual agenda that has come to dominate in the current era, under the banner of McCarthy’s terminology. (This state of affairs is surely, however, only temporary; the pendulum swings more in AI than

in most fields.)

But we need to move beyond the particular historical perspectives of McCarthy and Wiener.

We need to realize that the current public dialog on AI — which focuses on a narrow subset of industry and a narrow subset of academia — risks blinding us to the challenges and opportunities that are presented by the full scope of AI, IA and II.

This scope is less about the realization of science-fiction dreams or nightmares of super-human machines, and more about the need for humans to understand and shape technology as it becomes ever more present and influential in their daily lives. Moreover, in this understanding and shaping there is a need for a diverse set of voices from all walks of life, not merely a dialog among the technologically attuned. Focusing narrowly on human-imitative AI prevents an appropriately wide range of voices from being heard.

While industry will continue to drive many developments, academia will also continue to play an essential role, not only in providing some of the most innovative technical ideas, but also in bringing researchers from the computational and statistical disciplines together with researchers from other

disciplines whose contributions and perspectives are sorely needed — notably

the social sciences, the cognitive sciences and the humanities.

On the other hand, while the humanities and the sciences are essential as we go forward, we should also not pretend that we are talking about something other than an engineering effort of unprecedented scale and scope — society is aiming to build new kinds of artifacts. These artifacts should be built to work as claimed. We do not want to build systems that help us with medical treatments, transportation options and commercial opportunities to find out after the fact that these systems don’t really work — that they make errors that take their toll in terms of human lives and happiness. In this regard, as I have emphasized, there is an engineering discipline yet to emerge for the data-focused and learning-focused fields. As exciting as these latter fields appear to be, they cannot yet be viewed as constituting an engineering discipline.

Moreover, we should embrace the fact that what we are witnessing is the creation of a new branch of engineering. The term “engineering” is often

invoked in a narrow sense — in academia and beyond — with overtones of cold, affectless machinery, and negative connotations of loss of control by humans. But an engineering discipline can be what we want it to be.

In the current era, we have a real opportunity to conceive of something historically new — a human-centric engineering discipline.

I will resist giving this emerging discipline a name, but if the acronym “AI” continues to be used as placeholder nomenclature going forward, let’s be aware of the very real limitations of this placeholder. Let’s broaden our scope, tone down the hype and recognize the serious challenges ahead.

Michael I. Jordan

每天推荐一个 GitHub 优质开源项目和一篇精选英文科技或编程文章原文,欢迎关注开源日报。交流QQ群:202790710;电报群 https://t.me/OpeningSourceOrg