每天推荐一个 GitHub 优质开源项目和一篇精选英文科技或编程文章原文,欢迎关注开源日报。交流QQ群:202790710;微博:https://weibo.com/openingsource;电报群 https://t.me/OpeningSourceOrg

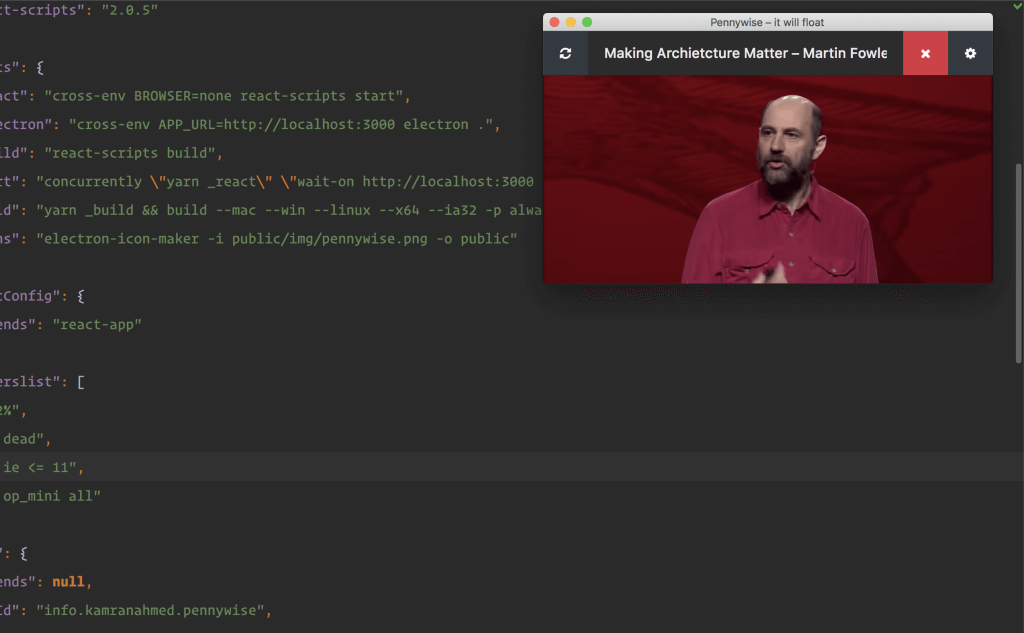

今日推荐开源项目:《永续魔法卡——悬浮 pennywise》传送门:GitHub链接

推荐理由:如果你想要一直看着某个窗口——在干着其他事情的时候,比如刷游戏的时候看一看新闻联播之类的,那么这个项目就能够帮上你的忙。它能够让你免受频繁切换的烦恼,一直将窗口悬浮在最顶部,只需要输入 URL,一切都会简单轻松。顺带一提,在一边写代码一边看教程的时候使用有奇效。

今日推荐英文原文:《Want To Be In The Top 1% Of IT Teams? Here’s What It Takes》作者:Vishnu Datla

原文链接:https://medium.com/devopslinks/want-to-be-in-the-top-1-of-it-teams-heres-what-it-takes-6f281b44b185

推荐理由:在现在这个时代如果想要成为优秀的团队,速度是必不可少的

Want To Be In The Top 1% Of IT Teams? Here’s What It Takes

Recently, one of our client’s Chief Information Officer commented that he wanted his team to be in the top 1% in the industry.

Soon after, our sponsor, their VP of IT, and I tried to unpack the CIO’s statements and get something tangible to help my customer deliver the CIO’s vision. We asked, what does it really take to reach that 99th percentile?

In a word, speed.

It wasn’t long ago that software companies could enjoy the luxury of moving slowly. Every two years, a new version of software would be released, CDs would be shipped to customers who would eagerly pop them into their disc drives and hit “install.”

And then? The whole two-year process would start all over again.

Today, however, if you want to be in the top 1% of IT teams, that approach is laughable, due to the new benchmarks of software delivery.

Companies like Amazon, Facebook, Netflix, and Etsy have blazed the trail to get their code from a developer all the way to an end user on a daily basis. The only way to get there is by implementing DevOps, refining processes, staying competitive, and applying pragmatic leadership goals.

It takes a ton of hard work, but if you’re passionate, strategic and confident enough, you’ll be able to pull it off.

Here’s how to go about it:

Grasp the importance of speed and agility.

Increasing the delivery velocity is a business imperative.

There have never been more tools and opportunities (along with online communities) to get help for those who want to move fast.

Today, a broke college kid with access to open-source software can build an app along with e-commerce integration in weeks. As an IT leader, you need to be a passionate and hungry college kid. Moving quickly allows you to challenge the Goliaths of the industry that can’t react as fast.

Take giants like Capital One and Bank of America, for example.

For a random consumer in Minneapolis, there really isn’t much of a difference between the two banks in terms of their services. But the mobile app software is really what tips the scales. If Capital One’s app keeps giving customers new features that they demand regularly, those customers will begin to move more of their business over to that platform and away from the competition.

It’s no longer beneficial to be quick, it’s actively detrimental to be slow. Any company that isn’t keeping pace is already on their way to extinction.

Create a sense of urgency to stay competitive.

Unfortunately, just understanding of the importance of velocity and speed is not enough.

You have to increase your velocity, not just within your team but within some dependent functions, too. In the SaaS software business, I see a new competitor enter our market every quarter — and any one of them has the potential to hurt our market share. A competitor is always knocking at the door. If we lose focus, even for a short time, someone is going to come to take a bite out of my business.

I know this from my own experience.

At one point, moving slowly affected our growth at my startup, AutoRABIT.

We were supporting several tech stacks with 100+ integrations, but we weren’t investing in DevOps or tools to support our platform with seven different modules (which are independent products in their own right).

Due to our divided attention and slow processes, we lost leadership on a couple of modules. Another company built a better module than us, and we were consistently slow and struggling — and maybe bit complacent. In fact, we ended up partnering with our competitor, and we now refer business to them.

While we have refocused and are revamping our core modules today, we lacked a sense of urgency and the 1% mindset we needed to be faster and nimbler.

It was a wake-up call for me.

Realize that Change Management is key.

After our failure, I knew I had to start practicing what I was preaching when it came to DevOps and cultural change.

The first thing we did was step back and spend time on planning. Our team began investing in training, tools, and processes, but most importantly in Change Management. We started automating and spending time and money on better processes, better people, better technology. We even increased our salary budgets to attract top talent and brought in a consulting firm to audit our process and service guidelines.

We had to tackle:

- Internal resistance to DevOps and culture changes.

- External pressure created by our innovation goals versus the external stability needs.

- Calculated risks in tools, new process, people churn, and the team’s breakpoints.

It wasn’t an easy journey.

But as a leader, you have to show your team what it means to be in the top 1%. You have to communicate the vision, the goals, and the way forward. You have to make sure every developer is getting better and enjoying what they do because you’ll only have success when your team is looking forward to coming into the office and achieving something every day, every week, and every month.

That’s how a top 1% team is born.

每天推荐一个 GitHub 优质开源项目和一篇精选英文科技或编程文章原文,欢迎关注开源日报。交流QQ群:202790710;微博:https://weibo.com/openingsource;电报群 https://t.me/OpeningSourceOrg