今日推荐开源项目:《简洁 Awesome-Clean-Code-Resources》

今日推荐英文原文:《Beautiful Code Principles》

今日推荐开源项目:《干净 Awesome-Clean-Code-Resources》传送门:GitHub链接

推荐理由:这个项目是一些关于如何写出干净代码——看起来很简洁,读起来也很简洁的代码的资料。包括细分到各种语言中的小技巧以及在这之上的书籍——描述那些不管是哪种语言要想写出干净代码都会有的共同点。了解这些小技巧有助于适应团队合作,举个最简单的例子,帮助其他人看懂你的代码。

今日推荐英文原文:《Beautiful Code Principles》作者:Pavle Pesic

原文链接:https://medium.com/flawless-app-stories/beautiful-code-principles-39420873eff8

推荐理由:书写良好代码的一些原则

Beautiful Code Principles

Writing beautiful code is often underestimated, especially by inexperienced developers. The main reasons are that writing beautiful code takes more time, and you won’t see its benefits right away.What is beautiful code?

Beautiful code is clean, well-organized, and simple to upgrade. It is easy to read, understand, and navigate. To create and maintain such code, I follow eight simple principles.1. Have coding standards

Coding standards are a set of coding rules. There is no universal coding standard, every product team might have its own written and unwritten rules. Among important ones, I would mention guidelines for- naming variables & naming methods,

- how to group methods & how to group classes,

- the order of writing methods,

- how to import dependencies,

- how to store data, so you would have a uniform code in every class.

This kind of code is more comfortable to understand. Coding standards give you consistency in all the projects you are working. If you are looking at some project from your company for the first time, you’ll know where to search the content you need. In the long term, coding standards save you a lot of time — from reviewing the code to upgrading features you haven’t worked on before, because you know what to expect.

Let’s see some good and bad examples of naming variables and methods:

// MARK: - Do

var cellEstimateHight = 152

var shouldReloadData = false

var itemsPerPage = 10

var currentPage = 0

// MARK: - Don't

var a = 152

var b = false

var c = 10

var p = 0

// MARK: - Do

func calculateHypotenuse(sideA: Double, sideB: Double) -> Double {

return sqrt(sideA*sideA + sideB*sideB)

}

// MARK: - Don't

func calculate(a: Int, b: Int) -> Int {

return sqrt(a*a + b*b)

}

Now one more example of Do and Don’t for groping your methods:

// MARK: - Do

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

self.prepareCollectionView()

self.addLongPressGesture()

self.continueButton.enable()

}

override func viewDidAppear(_ animated: Bool) {

super.viewDidAppear(animated)

self.showAlertDialogueIfNeeded()

}

private func prepareCollectionView() {

self.collectionView.register(UINib(nibName: "PhotoCollectionViewCell", bundle: nil), forCellWithReuseIdentifier: "PhotoCollectionViewCell")

self.collectionView.allowsSelection = false

}

private func addLongPressGesture() {

self.longPressGesture = UILongPressGestureRecognizer(target: self, action: #selector(self.handleLongGesture(gesture:)))

self.collectionView.addGestureRecognizer(longPressGesture)

}

func collectionView(_ collectionView: UICollectionView, numberOfItemsInSection section: Int) -> Int {

return self.selectedAssets.count

}

func collectionView(_ collectionView: UICollectionView, cellForItemAt indexPath: IndexPath) -> UICollectionViewCell {

let cell = collectionView.dequeueReusableCell(withReuseIdentifier: "PhotoCollectionViewCell", for: indexPath) as? PhotoCollectionViewCell

return cell!

}

// MARK: - Don't

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

self.prepareCollectionView()

self.addLongPressGesture()

self.continueButton.enable()

}

private func prepareCollectionView() {

self.collectionView.register(UINib(nibName: "PhotoCollectionViewCell", bundle: nil), forCellWithReuseIdentifier: "PhotoCollectionViewCell")

self.collectionView.allowsSelection = false

}

func collectionView(_ collectionView: UICollectionView, numberOfItemsInSection section: Int) -> Int {

return self.selectedAssets.count

}

func collectionView(_ collectionView: UICollectionView, cellForItemAt indexPath: IndexPath) -> UICollectionViewCell {

let cell = collectionView.dequeueReusableCell(withReuseIdentifier: "PhotoCollectionViewCell", for: indexPath) as? PhotoCollectionViewCell

return cell!

}

private func addLongPressGesture() {

self.longPressGesture = UILongPressGestureRecognizer(target: self, action: #selector(self.handleLongGesture(gesture:)))

self.collectionView.addGestureRecognizer(longPressGesture)

}

override func viewDidAppear(_ animated: Bool) {

super.viewDidAppear(animated)

self.showAlertDialogueIfNeeded()

}

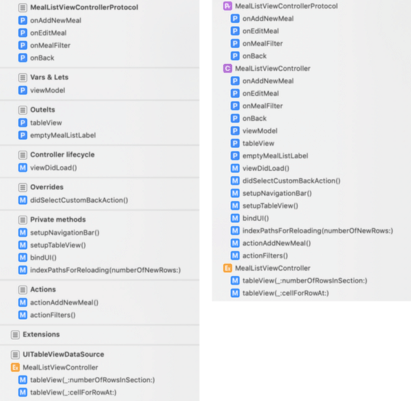

Also, when talking about coding standards, don’t forget the organization of your workspace. To navigate quickly, you have to organize your project functionally: create groups of files that relate to each other. Keep the same organization for all projects. So if you work on multiple projects, you don’t have problems with finding the resources you want.

How to create groups

2. Use self notation

This can be coding standard too, but I wanted to point out a few things about the concept.Firstly you have clear perspective what is global and what is local variable for the current scope. Allthow Xcode sets the different color for global variables, that isn’t good enough distinction for me. When using self notation, it’s much easier to recognize it.

In the other hand, if you have code with many handlers, you have to use self notation inside them. Using it outside of handlers too makes your code uniform.

3. Use marks for easier navigation

Marks are used for dividing functionality into meaningful, easy-to-navigate sections. And yet, not all developers are not using them. There are two types of marks in terms of preview with and without dash (-). Marks with it are preceded with a horizontal divider.

Navigation with and without marks

We use marks with das for creating sections, and if you want to create subgroups, we use marks without the dash.

Again, like in the first section, this code is easier to understand, navigate, and review. Code without marks or methods placed in the wrong section, shouldn’t be approved at the review.

4. Constants

There shouldn’t be any strings or any other constant in your classes. Constants are pieces of information that don’t have much value so you shouldn’t pay attention to it. Moreover, they can be quite long, in another language, so it makes your code unreadable.What you should do is to create a file with constants, create a coding standard for naming constants, group them using marks, and then use them in the classes. One more benefit of constants is that you can reuse them, and if there is a need for change, there is only one place to do it.

5. Class size

Depending on the project you are working on, you should predetermine class size. Ideally, a class shouldn’t be longer than 300 lines, without comments, but there will be exceptions, of course. Small classes are much easier to understand, manage, and change.To have small classes first, you have to think about architecture. In standard MVC it’s tough to have controllers that are smaller than 300 lines. That’s why you should try with other types of architecture like MVVM or Viper. There, controllers aren’t so massive because they are only responsible for presentation logic. Business logic is in other files.

However, be aware. Readability should always be the priority relative to class size. Your functions should also be small, easy to read and understand. You should have a maximum number of lines for function, and if the function has more lines than allowed, you should refactor it. Let’s see on practice:

// MARK: - Do

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

self.setupTextFields()

self.setupTableView()

self.bindUI()

}

private func setupTableView() {

self.view.backgroundColor = .red

self.tableView.dataSource = self

self.tableView.delegate = self

self.tableView.register(UINib(nibName: "MealTableViewCell", bundle: nil), forCellReuseIdentifier: "MealTableViewCell")

self.tableView.separatorStyle = .none

self.tableView.backgroundColor = .blue

self.tableView.contentInset = UIEdgeInsets(top: 0, left: 0, bottom: 80, right: 0)

}

private func setupTextFields() {

self.emailTextField.delegate = self

self.fullNameTextField.delegate = self

self.passwordTextField.delegate = self

self.passwordTextField.isSecureTextEntry = true

self.confirmPasswordTextField.delegate = self

self.confirmPasswordTextField.isSecureTextEntry = true

self.userRoleTextField.delegate = self

}

// MARK: - Don't

override func viewDidLoad() {

super.viewDidLoad()

self.emailTextField.delegate = self

self.fullNameTextField.delegate = self

self.passwordTextField.delegate = self

self.passwordTextField.isSecureTextEntry = true

self.confirmPasswordTextField.delegate = self

self.confirmPasswordTextField.isSecureTextEntry = true

self.userRoleTextField.delegate = self

self.view.backgroundColor = .red

self.tableView.dataSource = self

self.tableView.delegate = self

self.tableView.register(UINib(nibName: "MealTableViewCell", bundle: nil), forCellReuseIdentifier: "MealTableViewCell")

self.tableView.separatorStyle = .none

self.tableView.backgroundColor = .blue

self.tableView.contentInset = UIEdgeInsets(top: 0, left: 0, bottom: 80, right: 0)

self.bindUI()

}

6. Create reusable components

One more trick for having smaller, easier to understand classes is to create reusable components with the following characteristics:- It handles business processes

- It can access another component

- It’s relatively independent of the software

- It has only one responsibility

7. Design patterns

For solving some problems, there are already excellent solutions — design patterns. Each pattern is like a blueprint that you can customize to solve a particular problem in your code, and after a little bit of practice, quite easy to understand and implement. Design patterns make communication between developers more efficient. Software professionals can immediately picture the high-level design in their heads when they refer to the name of the pattern used to solve a particular issue.Every app needs a different set of patterns, but there are common ones that every app should implement — delegation, observer, factory, dependency injection.

8. Code review

While the primary purpose of code reviews should be functionality, we also need to take care about readability and organization of the code. If the code doesn’t compile to these principles, reject a pull request.Some tools can help you with code reviews like SwiftLint or Tailor, so I highly recommend using one.

Code reviews can take some time, but they are an investment for the future. New developers will learn these principles by reviewing your code, and by getting your feedback about theirs. Moreover, the clean code will save you time when you come back to change feature after a few months.

Be strict when reviewing and expect it from others when reviewing your code. If you don’t do so, you’ll create an atmosphere that it’s ok to make mistakes. Don’t merge code if it has flaws. Chances are you are going to forget to fix them.

Conclusion

The functional aspect of the code is an essential part of developing an app. However, to easily maintain and upgrade an app, the code has to be clean, organized, easy to read, understand, and navigate, or as we called it here beautiful.These are the principles I use to make my code beautiful. It sure takes more time to write and review, but it will save you more in the future.

下载开源日报APP:https://opensourcedaily.org/2579/

加入我们:https://opensourcedaily.org/about/join/

关注我们:https://opensourcedaily.org/about/love/

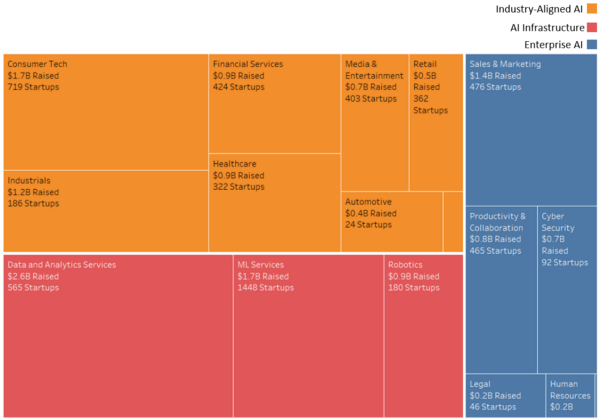

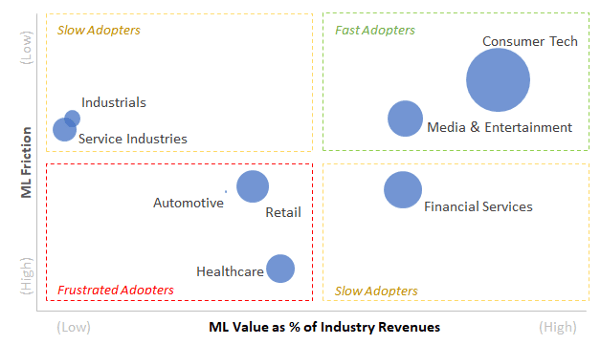

AI Venture Activity by Market | Source: Analysis of 7,192 “AI Startups” from Angel List

AI Venture Activity by Market | Source: Analysis of 7,192 “AI Startups” from Angel List

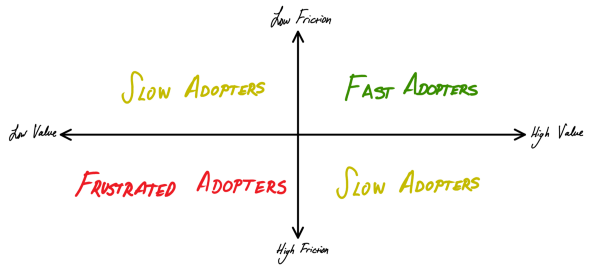

Rate of AI Adoption = f(AI friction, AI value)

So what does the road to mass adoption look like for your AI bet? This framework can be operationalized in a straightforward manner for any problem, venture, or industry. Here’s a more detailed breakdown.

Rate of AI Adoption = f(AI friction, AI value)

So what does the road to mass adoption look like for your AI bet? This framework can be operationalized in a straightforward manner for any problem, venture, or industry. Here’s a more detailed breakdown.

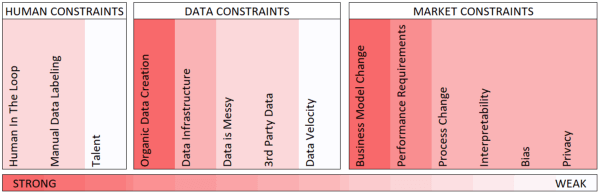

Estimated Magnitude of AI Frictions | Source: Interviews with AI Experts

Estimated Magnitude of AI Frictions | Source: Interviews with AI Experts

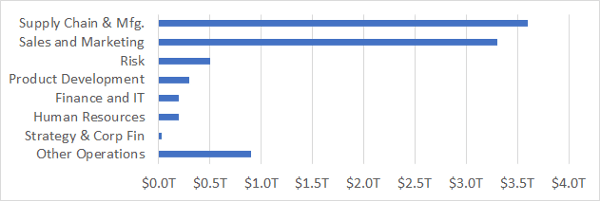

Value of AI by Use Case | Source: McKinsey Global Institute

Value of AI by Use Case | Source: McKinsey Global Institute

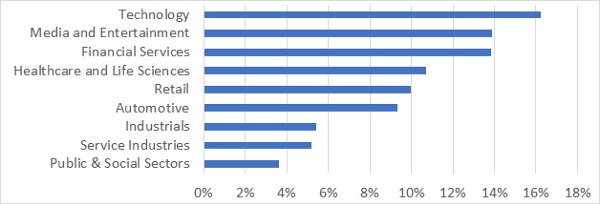

Value of AI as % of Industry Revenues | Source: McKinsey Global Institute

Value of AI as % of Industry Revenues | Source: McKinsey Global Institute

Based on my analysis, AI will roll out across industries in three waves:

Based on my analysis, AI will roll out across industries in three waves: