今日推荐开源项目:《做 ppt 的 nodeppt》

今日推荐英文原文:《How to Solve Any Code Challenge or Algorithm》

今日推荐开源项目:《做 PPT 的 nodeppt》传送门:GitHub链接

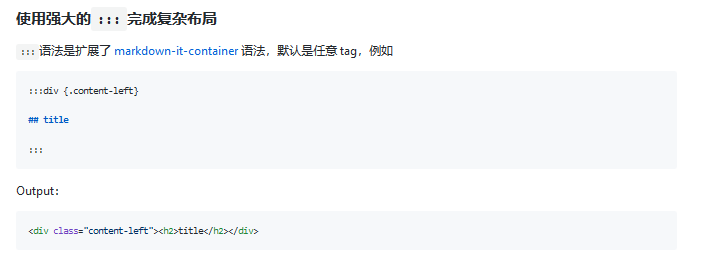

推荐理由:一个能用 markdown 文件生成 PPT 的项目,支持各种样式,布局以及方便强大的语法。它还扩展了 markdown-it-container 语法,简而言之,你可以像通过 HTML 里的各个标签以及它们的 class 来控制样式一样控制一段 markdown 文件的样式,而这能够更灵活的控制生成的 PPT 的效果。

今日推荐英文原文:《How to Solve Any Code Challenge or Algorithm》作者:James Dorr

原文链接:https://medium.com/swlh/how-to-solve-any-code-challenge-or-algorithm-c66e0bed9dc9

推荐理由:解决代码或者算法问题的通用步骤

How to Solve Any Code Challenge or Algorithm

“Know algorithms!” When you’re searching for jobs in tech, this is frequent advice. Most articles about algorithms and coding challenges seem to recommend practicing them so much that you‘ll recognize almost anything an interviewer might ask you. Practicing algorithms and explaining the solutions out loud are very important — you want to be able to explain your ideas — but problem solving in software and web development requires more than rote memorization.Computer Science is a science of abstraction. -Alfred AhoGood code is abstract, so let’s apply that same logic to our problem solving! These steps are not specific and can be applied to most code challenges.

Being abstract is something profoundly different from being vague… The purpose of abstraction is not to be vague, but to create a new semantic level in which one can be absolutely precise. -Edsger Dijkstra

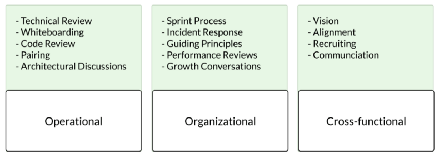

Summary

We only need a few oft-repeated steps to solve any code challenge.- Understand the Problem

- Choose a general direction

- Identify what you can do

- Search for what you cannot do (and need to do)

- After finishing, try to improve it

Understand the Problem

Thoroughly understand the problem before you dive in. Ask questions, if necessary! You can do it! They wouldn’t ask this if you couldn’t.I chose this problem for many reasons. First of all, this question isn’t obvious. It’s not a question we have probably ever been asked before. Read it as many times as needed and study the expected input and output (if available).

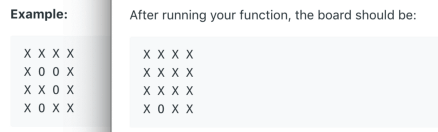

This problem wants us to only leave Os that have a path to a border. “Surrounded Regions” of Os are converted to Xs.

Change the matrix on the left to the matrix on the right

Choose a general direction

When working on projects, this might mean deciding where the solution should go. Is this better suited for the frontend or the backend? In the frontend, is this the right component for that logic? In the backend, how can we use RESTful routes? Do we want that RESTful route to always perform this logic?For LeetCode, I chose JavaScript because I am trying to fine-tune those skills.

Identify What You Can Do

Do anything you can do that moves towards solving the problem, no matter how small. Even getting “Hello, World!” on the screen is better than a blank screen.Especially if you’re feeling overwhelmed, make sure the code is behaving as expected. Console.log or print! Maybe we don’t know much, but we now know the input (if we didn’t before) and we know that we wrote our function correctly. Any confidence boost is welcome!

For the LeetCode problem, I used console.log to print the board, then its rows, and finally the characters in the rows — just to make sure I was iterating over the entire input correctly.

What can we do next? A huge, huge part of problem solving is breaking it down into smaller chunks. Even if it’s minuscule, what do you know how to do next?

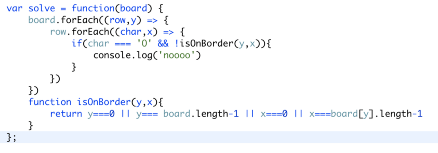

I chose to see if I could write code to identify which Os were on the border.

function isOnBorder(y,x){

return y===0 || y===board.length-1 || x===1 || x===board[y].length-1

}

This code will console.log(‘noooo’) every time there is an O in the interior

Great! What small step can we take next? Let’s check that Os neighbors to see if they are Os!

The function checkFriendsOnBorder(y,x) prints out ‘VEIN!’ if the O has a neighboring O

I also put in comparisons at the beginning of the “if” statements because I knew JavaScript would throw an error or give the wrong information if the indices were negative or higher than the length of the arrays. But how would the indices be past safe ranges if this function was only run on Os that were in the interior, not on the border?

The intent was to eventually iterate over an array and add all of the O neighbors to that array, thus moving across the “board,” finding the group of Os that the original interior O belonged to. Then, if any of the Os were on the exterior, that original O could stay. However, this got confusing and ugly quickly, so there must be a better way. If you’re feeling confused during your own projects, it’s time to circle back to the steps Understand the Problem and Choose a General Direction, or maybe a more specific direction, now. Here, we will continue and I will explain my problem solving chronologically.

Search for What You Cannot Do

If you have an idea but are not sure how to implement it, search for the answer online! Maybe you haven’t learned a certain function of your computer language yet, or maybe someone has a piece of the puzzle you can borrow!In this problem, I searched for iterating over a growing array and found that functions assume the source data is not mutated, so that was a no-go. My own experiments within LeetCode yielded similar results — using “array.forEach…” never continued with the information that was added (.push()) onto the array, but “for(let i=0;…” occasionally did. I didn’t understand why the “for” loops were inconsistent, so I labeled that approach unlikely to succeed.

Next, I tried to use recursion and got errors because the Os were looping infinitely back and forth with their neighbors. Then I made arrays of “veins” for each O to make sure the code was not running over any O twice while making the vein. That also taught me that JavaScript arrays cannot use .includes([‘an’,’array’]) or .includes({an: ‘object’}) because they check for matching memory locations, not values.

In short, you can learn a ton from this step, and that inspired me to combine a few of the above ideas.

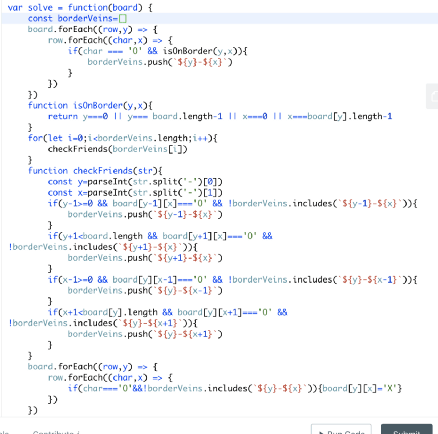

My first successful solution

First, I iterated over each character on the board and put the Os that were on the border in an array to be iterated over later. I put the coordinates of the Os in the array because they were necessary for moving across the board and changing the character, if necessary. Those coordinates had to be in a string to be found by .includes(), so I separated them by a dash just in case some test boards had indices in double digits.

Then, I used a “for” loop to iterate over the border Os and add all of their neighboring Os to the same array (still in the crazy string format). For some reason, I was still having trouble with recursion, so I used a “for” loop, instead. This “for” loop worked with the expansion of its source array, gathering all of the Os with any degree of separation from the border. It checked to make sure not to add them twice, otherwise we would be in an infinite loop.

Lastly, the code iterated over the board characters again and changed each O to an X if its coordinates were not in the borderVeins array.

Try to Improve It

Success! I clicked “submit” and saw “Accepted.” Yes! And it also said “Faster than 15% of submissions” and “Your memory usage beats 32% of submissions.” We can do better!Play around with the code! Try to make it more efficient.

After that, look at some other people’s answers! Both LeetCode and CodeWars have other answers available. I clicked on the answer with the most votes and looked at it just long enough to see that

- They iterated over the code multiple times, changing border Os and their groups to 1s and then back to Os at the end

- They used recursion!

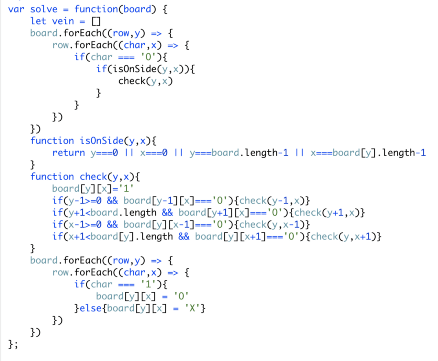

A more optimized solution

A more optimized solution

Faster than 91.12% of submissions, memory usage less than 100% of submissions

Faster than 91.12% of submissions, memory usage less than 100% of submissions

Ta-da! The code looks much cleaner, and LeetCode tells us that it also runs faster with less memory usage. Wonderful!

Takeaways

Another reason I chose this problem was because it was not easy. I got discouraged, but I kept telling myself I could solve it, and I did! I also understand recursion better, as a result. I don’t remember what I was doing wrong before, but now I have successfully used recursion in JavaScript, and I have that tool in my toolbox!The best reward is proving the little negative voices in your head wrong. You did it! It was just imposter syndrome. You can solve these, as long as you keep believing you can. Stick to these steps, with an emphasis on taking small steps that you know you can accomplish, and go solve more problems!

下载开源日报APP:https://opensourcedaily.org/2579/

加入我们:https://opensourcedaily.org/about/join/

关注我们:https://opensourcedaily.org/about/love/