开源日报 每天推荐一个 GitHub 优质开源项目和一篇精选英文科技或编程文章原文,坚持阅读《开源日报》,保持每日学习的好习惯。

今日推荐开源项目:《游戏引擎GDevelop》

今日推荐英文原文:《Is Learning Feasible?》

今日推荐开源项目:《游戏引擎GDevelop》传送门:

GitHub链接

推荐理由:想要设计一款游戏吗,即使你没有编程基础?试试 GDvelop 吧。或者,如果你是资深程序员?没有关系, GDvelop 完全开源免费,你可以修改其源代码,从而实现更多的功能。其游戏制作界面相当易用,零代码,只需要基本的逻辑就能创作出各种有意思的游戏。 GDevelop 采用拖曳与事件方式,让你快速加入游戏中的物件并且为其安排事件行为,可以用非常视觉化的方法制作游戏,支持本机(SFML) 与 HTML5(网页) 两种游戏引擎。

今日推荐英文原文:《Is Learning Feasible?》 作者:Eugen Hotaj

原文链接:

https://towardsdatascience.com/is-learning-feasible-8e9c18b08a3c

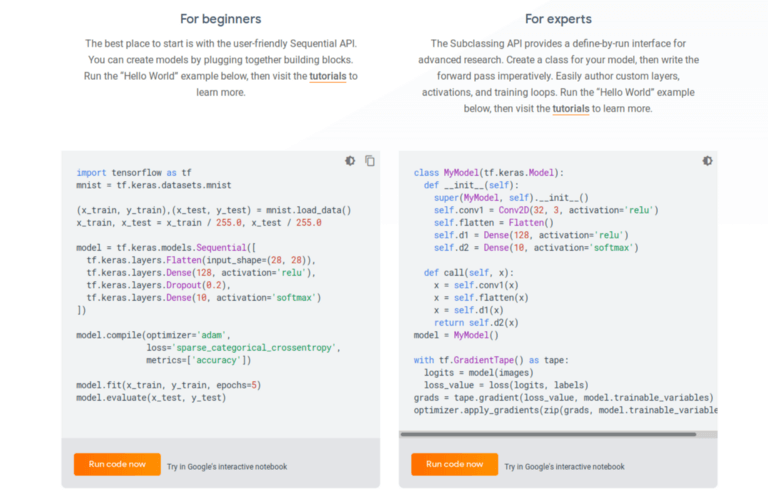

推荐理由:即将步入2020,机器学习早已被大肆炒作,但是,机器学习真的已经发展到人们想象的那么先进了吗?Eugen Hotaj向我们提出了“机器学习真的可靠吗”的问题,并从从机器学习的原理出发进行阐述。

Is Learning Feasible?

A quick foray into the foundations of Machine Learning

It’s late 2019 and the hype around Machine Learning has grown to unreasonable proportions. It seems like every week a new state of the art result is reported, a slicker Deep Learning library surfaces on GitHub, and OpenAI releases a GPT-2 model with more parameters. With the mind-bending results we’ve seen so far, it’s hard not to get swept up in the hype.

Others, however, warn that Machine Learning has overpromised and underdelivered. They worry that such continued action could cause research funding to dry up, leading to another Artificial Intelligence winter. This would be bad news indeed. Therefore, in order to curb the enthusiasm around Machine Learning, and single-handedly prevent the inevitable AI winter, I will convince you that

learning is not feasible.

This article was adapted from the book “Learning from Data” [1].

The Learning Problem

Fundamentally, the goal of Machine Learning is to find a function g which most closely approximates some unknown target function f.

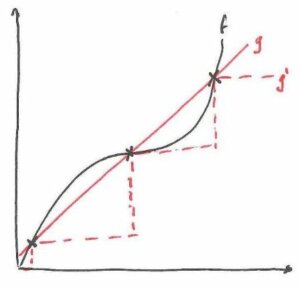

For example, in Supervised Learning, we are given the value of f at some points X, and we use these values to help us find g. More formally, we are given a dataset D = {(x₁, y₁), (x₂, y₂), …, (xₙ, yₙ)} where yᵢ = f(xᵢ) for xᵢ ∈ X. We can use this dataset to approximate f by finding a function g such that g(x) ≈ f(x) on D. However, the goal of learning is not to simply approximate f well on D, but to approximate f well everywhere. That is, we want to generalize. To drive this point home, take a look at the figure below.

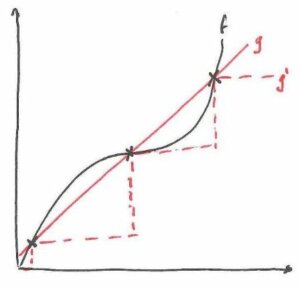

(Two different approximations to the function f.)

Both g and g’ perfectly match f on the training data (denoted by the “x”s in the figure). However, g is clearly a better approximator of f than g’. What we want is to find a function like g, not g’.

Why Learning is not Feasible

Now that we’ve set up the learning problem, it’s worth stressing that the target function f is genuinely unknown. If we knew the target function, we wouldn’t need to do any learning at all, instead we would just use it directly. And, since we don’t know what f is, regardless of what g we ultimately chose, there is no way for us to verify how well it approximates f. This may seem like a trivial observation, but the rest of this article will hopefully demonstrate its ramifications.

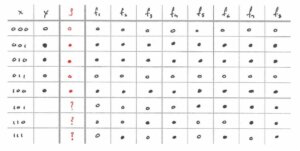

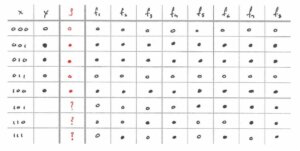

Suppose that the target function f is a Boolean function with a three-dimensional input space, i.e. f: X → {0, 1}, X = {0, 1}³. This is a convenient setup for us to analyze since it’s easy to enumerate all possible functions in the space [2]. We want to approximate f with a function g by making use of the training data below.

(Training data available to approximate f. Here, x is the input and y = f(x). For clarity, we use ○ to indicate an output of 0 and ● to indicate an output of 1.)

Since we want to find the best possible approximation to f, let’s only keep the functions in the space which agree with the training data and get rid of all the others.

(All possible target functions which agree with the training data.)

Great, now we’re down to only 8 possible target functions, labeled f₁ to f₈, in the figure above. For convenience we’ve also kept around the labels of the training data. Notice that we don’t have access to the out of sample labels since we don’t know what the target function is.

Now the question becomes, which function do we choose as g? Since we don’t know which f is the real target function, maybe we can try to hedge our bets by choosing a g which agrees with the most potential target functions. We can even use the training data to guide our choice (learning!). This sounds like a promising approach. But first, let’s define what we mean by “agrees with the most potential target functions.”

Learning the best hypothesis

In order to determine how good a hypothesis (i.e. a choice of g) is, we first need to define an objective. One straightforward objective is to give a hypothesis one point each time it agrees with one of the fᵢ on the out of sample input. For example, if the hypothesis agrees with f₁ on all inputs, it gets 3 points, if it agrees on 2 inputs, it gets 2 points, and so on for all fᵢ. It’s easy to see that the maximum number of points a hypothesis can score is 24. However, to score 24 points, the hypothesis would have to agree with all possible target functions on all possible inputs. This is, of course, impossible since the hypothesis would have to output both 0 and 1 for the same input. If we ignore impossible scenarios, then the maximum number of points is only 12.

The only thing left to do now is pick a hypothesis and evaluate it. Since we’re smart humans, we can look at our training data and “learn” if there is a pattern there. The XOR function seems to be a good candidate: output 1 if the input has an odd number of 1s, otherwise output 0. It agrees with the training data perfectly, so let’s see how well it does on the objective.

(Computing the objective value for the XOR hypothesis.)

If we go through the exercise, we see that, on the out of sample data, XOR agrees with one function exactly (+3 points), three functions on two inputs (+6 points), three functions on one input (+3 points), and does not agree at all with one function (+0 points), giving a grand total of 12 points. Perfect! We were able to find a hypothesis which achieves the highest possible score. There may be other hypotheses that are as good, but we’re guaranteed that these is no hypothesis which is better than the XOR. There may even be hypotheses that are worse which get less than 12 points. In fact, let’s find one such bad hypothesis just so we can sanity check that XOR is indeed a good candidate for the target function.

The worst possible hypothesis?

If XOR is one of the best hypotheses, an obvious candidate for a bad hypothesis is its exact opposite, ¬XOR. For each input,¬XOR outputs 0 if XOR outputs 1 and vice versa.

(Computing the objective value for the ¬XOR hypothesis.)

Going through the exercise again, we now see that, on the out of sample data, ¬XOR agrees with one function exactly (+3 points), three functions on two inputs (+6 points), three functions on one input (+3 points), and does not agree at all with one function (+0 points), giving a perfect score… again. In fact, any function we choose as our hypothesis will get a perfect score. This is because any function must agree with one — and only one — of the possible target functions exactly. From there, it’s easy to see that any fᵢ will match three of the other fᵢ on two inputs, three on one input, and one on no inputs.

What’s shocking is that we can choose a perfect hypothesis without even looking at the training data. Even worse, we can choose a hypothesis which completely disagrees with the training data, and it would still achieve a perfect score. In fact, this is exactly what ¬XOR did.

This means that all functions are equally likely to agree with the target function on the out of sample data, regardless of whether they agree on the training.

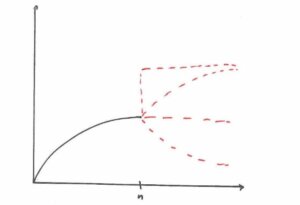

Put another way, the fact that a function agrees with the training data gives no information whatsoever on how well it will agree with the target function out of sample. Since all we actually care about is performance out of sample, why do we even need to learn? This isn’t just true for Boolean functions either, but for any possible target function whatsoever. Here’s a figure which illustrates the point more clearly.

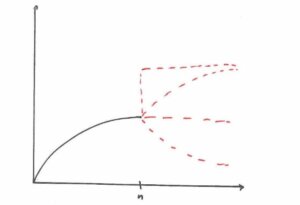

(Valid values the function f could take for input > n.)

Knowing f on (-∞, n) tells us nothing about its behavior on [n, ∞). Any of the dotted lines could be valid continuations of f.

Probability, the Saving Grace

Maybe this is the part you expect me to say that it’s all been a huge joke and explain how I pulled the wool over your eyes. Well, it’s no joke, but clearly Machine Learning works in practice, so there must be something we’re missing.

The reason learning “works” is due to a crucial, fundamental assumption known as the i.i.d assumption: both the training data and the out of sample data are independent and identically distributed. This simply means that our training data should be representative of the out of sample data. This is a reasonable assumption to make: we can’t possibly expect what we learn on the training data to generalize out of sample if the out of sample data differs significantly. Put more simply, if all our training data comes from y = 2x, then we can’t possibly learn anything about y = -9x² + 5.

The i.i.d assumption also roughly holds in practice — or at least does not break down too significantly. For example, if a bank want to build a model using information from past clients (training data), they can reasonably assume that their new clients (out of sample data) won’t be too different. We didn’t make this assumption in the Boolean function example above, so we couldn’t rule out any fᵢ from being the true target function. If we do, however, assume that the output of the target function on the out of sample data is similar to the training data, then clearly f₁ or f₂ most likely to be the target function. But of course, we can never know for sure ?.

Eugen Hotaj

November 29, 2019

下载开源日报APP:

https://opensourcedaily.org/2579/

加入我们:

https://opensourcedaily.org/about/join/

关注我们:

https://opensourcedaily.org/about/love/